The clatter of building materials being delivered to my neighbor interrupted my empty-headed stare into the woods during my sit spot meditation this morning. It also startled several chipmunks who, I guess because they were unsure of what that sound meant, started chuck-chucking in almost unison. Hearing their call, a red squirrel froze on the hemlock branch she was traversing. Only one young chipmunk continued to scurry past me. He has not, I guess, learned the ways of the woods and did not listen to his kin’s warning that there might be a predator about. I, however, was listening to the chipmunks.

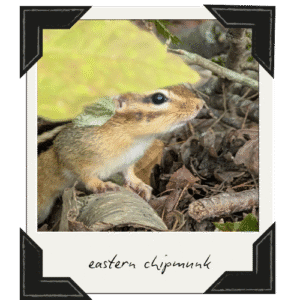

The eastern chipmunk (Tamias striatus) is a rodent in the family Sciuridae, the squirrels, and is found in the eastern half of the United States and southern Canada. “Chipmunk” is an adaptation of their name in Ojibwe, one of the indigenous languages of the Algonquins, which means “descends trees headlong,” as chipmunks and other squirrels are apt to do.

Unlike tree squirrels, however, chipmunks spend most of their time on the ground and live in burrows. The land near where I sit has many holes, each belonging to a different chipmunk. Chipmunks are solitary creatures and vigorously defend their territories, so each tunnel heads off in a different direction. I often witness one chipmunk chasing another and hear the quick chorus of trills and squeals that identifies a territorial dispute.

Chipmunks are community minded when a predator shows up, though. Instead of a safer silent retreat, a pursued chipmunk lets out a trill while running to warn the others. When there is danger, the chipmunks are usually the first to sound the alarm.

Chipmunks are community minded when a predator shows up, though. Instead of a safer silent retreat, a pursued chipmunk lets out a trill while running to warn the others. When there is danger, the chipmunks are usually the first to sound the alarm.

A rapid chuck-chuck-chuck warns of a predator above, such as a hawk. A slower chip-chip indicates the danger, perhaps a fox, is on the ground. Once one starts, other chipmunks join in, spreading the warning through the woods.

The squirrels and birds listen, too. Once the chipmunks start, the red squirrels begin chattering, and soon grey squirrels are barking from the safety of the trees. Fading blue jay caws indicate their retreat. Species normally squabbling over food and space work together to spread the word.

While I have no fear of hawks or foxes, listening to the chipmunks helps me tune into the activity in the woods and reminds me to engage in active listening throughout my day. Most humans rely heavily on their visual sense, but I have found that to feel part of all life around me requires more than just observation. To practice this in human conversation, I close my eyes against the visual distractions and hear both the words being spoken and the emotional tone. Actively listening provides deeper connection and understanding.

This morning, my listening revealed other sounds that indicated some kind of construction would soon begin next door. The rumble of internal combustion engines marked vehicles passing by on the road. Faint peep-peeps from the pigeon shelter revealed when one of the feral pigeons arrived to feed her babies. When I closed my eyes and really listened, I could even hear the thump-thump of bass coming from my husband’s office, letting me know he was playing the electronic music that gets him into “programming mode” while he codes.

Listening in this way reminds me that the dichotomy between the human world and nature is a false one. The chipmunks certainly do not recognize any division. They reacted to the human-made sound just as they would any other noise that deviated from the baseline hum of life in the woods. Since they did not react to the sounds of cars driving by, I can assume that our vehicles are now part of that hum. There are few places, really, where our human sounds have not penetrated but, by listening actively and openly to chipmunks, and all of life, their place, and mine, in the natural world is revealed.